[O]ne thing we all have in common as humans is the need to connect with others… even if the discovery only [leads] to being able to look into eyes that looked like mine for a minute. I felt this need to connect on a cellular level and the reason was indefinable to me.

– Annette L Becklund, Ancestry Discoveries (2023, p. 8)

My parents had met through my godmother Merrily’s parents Doris and Chuck. Doris was a sort of “mother hen” to a collection of teens and 20-somethings including Mom and her nephew Jim, and Chuck was Pops’ supervisor in selling Monarch gas ranges as a traveling salesman.

These four people were the ones Pops confided in when my non-premature birth – a full six weeks before when I had been expected to arrive – forced this young, newly married, and giddily happy couple to make unexpected – important and life-changing – decisions.

Merrily and Jim survived the other four adults who shared confidences about and pledged fidelity to the kiddo at the heart of reckonings and conversations. Only 15 when she became my godmother six weeks later, Merrily has been a constant presence in my life – starting with sending dolls from her travels around the world, tickets for short-hop flights in Michigan and Minnesota, and travel books to spark my own urge to visit, really visit, new places. Each gift was a perk from her work in the 1960s at the Pan American offices in New York City. Whether building her career in New York or a travel agency in Honolulu, Merrily came home every summer and Christmas each year, wrapping me into some part of her time in Minnesota.

Once I became a 20-something, we added letters, cards, and emails to our ways of connecting. And most of the last 20 years, we have talked and/or texted every week.

When I became a 50-something, both of our mothers died in the same year, and we began to travel together in between conversations – heading to England, Paris, Amsterdam – all second or third regurn visits for her, and places new to me.

As a 60-something, that darn DNA test opened a new conversation for us starting with an April 2019 dinner meet up we’d already arranged when my godmother was in town to fly out for a next adventure. Nearing the end of our conversation that day Merrily reminded me of a letter I’d written shortly after Mom, Pops and I had completed a 1967 trip that included Washington, DC, her flat in Manhattan, and time with Alexander cousins on Long Island. Neither of us remembers the letter exchange clearly, but do recall the main thread linking to my wondering “if Pops was just a nice man who married my Mom even though she was pregnant,” and her responding with something akin to “This is a question for you to share with your parents.” I didn’t raise the question in 1967, and as I talked with my godmother I recognized that question came alive for me on the way to New York, and remained for another decade of looking to find Alexander-Stafford-Evans-Svelstad in my face occupied my mind and soul.

That 1967 summer, we’d made our way to New York via a drive through southern states with Mount Vernon and Washington, DC, as stops before New York. Passing through Kentucky or Tennessee, Pops told us about being sent to the “Negroes Only” balconies, drinking foundations, and diners while in Leeds, Alabama, on Navy leave during 1950s service in Korea. It was his thick, nearly black wavy hair and dark olive complexion – still darker from conducting most of his Navy service outdoors – that led people “to take me to be a light-skinned black man.”

Standing in 1967 at the Eternal Flame and Lincoln Memorial, this just four years after JFK’s assassination and MLK’s “I Have a Dream Speech” at the foot of the Memorial., took on a new significance after hearing that story. We’d watched these events unfold together, as we would the RFK and MLK assassinations a year later. While the visual and felt memories of visit to these soul sites remain strong in me, it’s a traffic accident on our way out of the District that I can still play as a frame-by-frame Super 8 movie.

That traffic accident? A truck without brake lights and a rudimentary wooden box behind a rusted blue cab stopped abruptly. Our still-new family car got stuck up under the box, and the car behind us dented a bumper. As Pops left the car, looking to separate the truck and our car, white police on patrol approached the handful of black passers by who had joined the white drivers to help Pops. The patrol looked into our car – seeing a so very white skinned, light brown haired woman in the front seat, and a light skinned child with nearly black curly permed hair in the back seat – and ordered the black men to move away, to let the other two drivers help Pops free our car, and wrote Pops a ticket for careless driving. Clearly Pops, the black appearing man in the accident scuffle, was at fault. It was the n-words they used to order the black men away that remain seared in my head and heart, as well as Pops’ earlier words about being “taken for black.” Not mis-taken. Just taken.

Was I taken that day to be the child of a biracial couple, the Loving vs. Virginia case that struck down miscegenation laws having been struck down just weeks before? Perhaps.

Was that the day I began letting myself wonder about whose face elements I carried? about whether Pops was “just” that nice man who married my “happened to be pregnant at the time” mom? about what my parents were saying to each other when they argued making sure to me as much out of my hearing range as possible? I think yes.

That searching for my face, specifically searching my eyes and nose, is part of my August 2000 eulogy for Pops, recalling a moment just after Grumpy’s 1976 funeral:

My grandmother Hannah caught me in front of the bathroom mirror, glancing from an assortment of photos in my left hand to my reflection in the mirror. I spoke with the urgency of someone caught in the midst of a bad deed: “I need to see you and my dad in my face. When you’re not with me, when you’re both gone, I need to see you in my face.” Gram touched my brow. “Let me have these for a minute,” she said, removing my glasses. “You look just here, just from that short bridge of your nose to the brow. Just there. See the way the bones in your eye sockets make a perfect half circle above the eyelids, the way the corners of your eyes rise to meet your eyebrows in a perfect circle when you smile, the way your slim nose bridge gives way to that wide, flat brow. Those hazel eyes. See that.” And I did. “How can you not see that you are your father’s daughter and my granddaughter when you look yourself in the eyes? Don’t think Alexander, look for my grandma’s family, look for Evans’ eyes.”

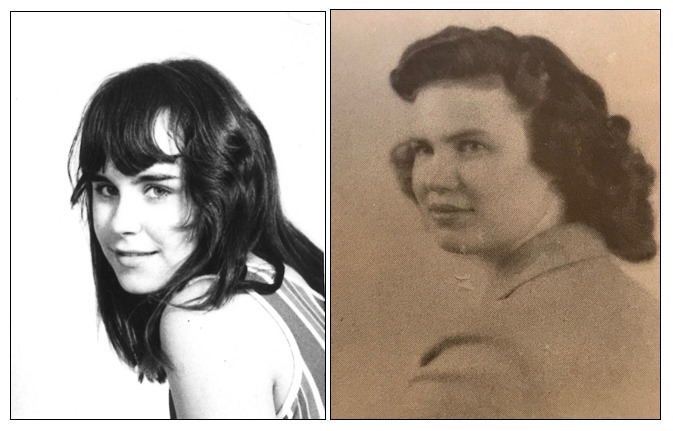

More than how their eyes looked or matched actual eyes, it was how those eyes looked on the world that mattered to me. And, then, in August 2019, I found the center of my face – nose, lips, chin – via a photograph of biodude’s older sister, Jeannine.

That’s her high school photo age 17 on the right, and on the left, 17-year-old me in self portrait for Norm Gullickson’s photo class. I recognized the middle of my face for the first time. Odd, that experience. A nose just is a nose, right? For me, it’s been a data gap, one that had been filled in with “You just have your own unique nose” whenever I observe that my nose doesn’t match Mom’s or her sisters, each with a tiny cartilage hook at the end, and was far from aligning with the bigger, broader, flared nostril boats of Pops’ families and of biodude and his father.

Finding the center of my face, particularly my nose didn’t make me part of biodude’s Poole-Mischke family. It did ground me a bit in understanding how I came together biologically. And it did prompt me to ask my one biodude contact about Jeannine and Marie – “You would have liked them. Jeannine was quite different from her brother, and Marie was super smart and warm.” I grew comfortable referring to them as my aunt and grandmother, which was helped as I searched a US newspaper database for references to each. I found articles about Jeannine as she became a nurse, as she moved to California, met and married a thoracic surgeon, and took on philanthropic work by heading medical school scholarship fundraising efforts that featured, for example, first time US viewing of French Impressionist artworks, auctioning needlework created by men, and recognition of USC alumna Pat Nixon, the then FIrst Lady. And Minnesota newspaper articles reporting on Marie’s work as a community organizer, ace card player, and co-owner and main buyer for Mildred’s, a women’s apparel shop in Wells, Minnesota.

Sometimes the briefest moments capture us, force us to take them in, and demand that we live the rest of our lives in reference to them.

– Lucy Grealy, Autobiography of a Face (1994, p.89)