Partly on thinking about Eve Sturges’ journal question

“How Has This Experience Changed the Way You See the People Who Raised You?”

In early 2018, Kathy, a newly identified maternal cousin Ancestry match, sent a message asking whether I might be able to answer some questions about her mother’s 1934 birth or adoption, maybe even about the person listed as birth mother. I could help because my Ancestry focus was on building a genealogical record for the maternal family we shared – and because I knew the particulars of that adoption story. Up to that point, considering who and what I might learn about in Ancestry’s list of DNA matches could wait.

With one click I was paying new attention: Pops’ family members who had also spit tested weren’t there. A pair of surnames I recognized from Mom’s hometown were instead listed as paternal matches. Fuck. Doubly so. That act of spitting had moved me into genetically “gone missing” in one lineage – the paternal raising family who shaped the metaphorical bones, heart, soul, and brains of me. And slammed me into a recognition that I was missing – actually never present – in another.

*** *** ***

There seems to be one person gone missing in every Alexander-Evans-Stafford-Svelstad generation, starting with Amanuel Stafford, the Scot-Irish immigrant skilled in wrought iron work who married Sophia Clark in 1839, much to the distress of her well-placed New England family. Amanuel’s going missing began with his wife’s death, and her week-placed family seeking guardianship of their children, ages two and three years old.

His daughter Lucy – sister to my much documented great-great grandfather – went missing from records, if not also from family, for two decades, and is now only vaguely traceable with a late in life marriage, and a pauper’s death record. Marriage and work aspects of Amanuel’s granddaughter Edna’s life are missing or misrecorded, despite her role as family documentarian. Two great grandsons chose exile on reaching age 21 over living near their father. His great-great grandson Richard, Puzzy in my life, had gone missing at age 38. And in my generation of great-great-great grandchildren – we seven cousins have mostly been missing from each other because of one uncle’s actions impacting his brothers’ families and his own.

For all those not found during a lifetime, the current genealogists in this family have looked to records for creating stories about where and who our missing might have been.

*** *** ***

My stash of photos say I met my Tracy family at my baptism in the Methodist church across from the homeplace. Looking now at that 1957 photo, it’s Pops, Mom holding me-the-baby, Puzzy, my uncle-godfather, and Merrily, the godmother who knew my actual birth story even then.

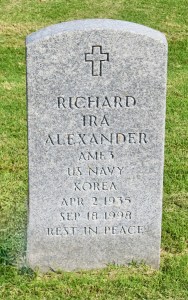

Although Puz is smiling directly into the camera, he is not relaxed. Just discharged from the Navy, he is home from Korea with a GED, soon to begin his own new life in California where he will make a life that includes coming out as artist and homosexual in 1950s America. His sporadic 1960s presence came about through brief visits including his husband Carl, gifts of books about art, and holiday cards or phone calls. As a gay man in middle America, he had chosen to combine physical exile with psychological presence.

Romantic relationships end, and with them, sometimes, family exiles return home as Puz did in 1972. His purple Gremlin stuffed with boxes to take up residence in the homeplace bedroom that otherwise served as a storage space. A late-spring photo marks the start of this return.

A photo dated 1972 marks the start of this return. That moment shows us gathered at the dining room table for dinner, that hearty midwest middle-of-the-day meal: roast turkey, mashed potatoes and gravy, cole slaw, white bread, whole milk, with the empty cake stand at the backside of the photo that promises an appearance of angel food cake with strawberries after the table is cleared. Mostly it shows that Puzzy and I have made them all laugh.

What’s not photographed includes Puz and I wandering in the backyard gardens talking about art and poetry. I would ask whether his visit home might be short or indefinite; he would shrug his shoulders. We two would assemble sandwiches for supper on the porch where family conversations would turn to weather, gardens, neighbors, birds, and the evening newscast. As always, family Saturdays would end with Scrabble, Gram winning and Pops making up new words to increase his score. That particular weekend, I began planning to come out to Puz, my fairy godfather.

Sometime before Easter 1973, Puz had left Tracy, no one telling Mom, Pops, Dave or me until we arrived for the holiday weekend. He was 38. I was 16.

He was the first Stafford in my life to go missing.

*** *** ***

With the Ancestry DNA test in 2016, I was joined another Stafford-Evans cousin who was hoping to turn up Welsh relatives, and to pick up the gone missing searches we inherited from Great-Great Aunt Edna, who built on oral stories to become the family’s first genealogist.

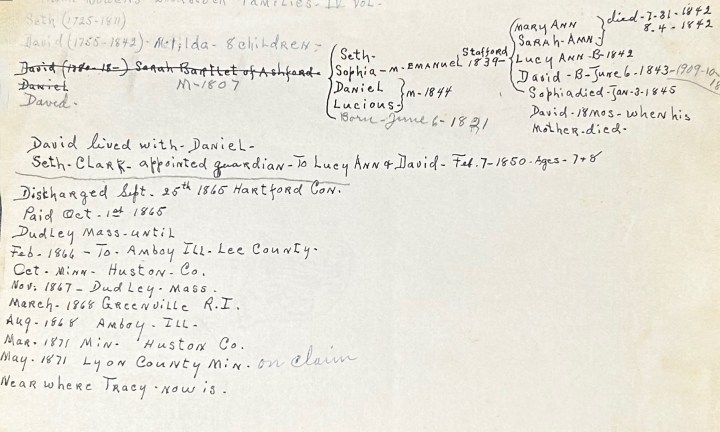

Finally looking at the DNA results in 2018, I reviewed folders with Edna’s handwritten notes and onion-skin paper copies of formal requests for research assistance or specific documents that might be housed in New England research libraries and historical or genealogical organizations. She persistently sought any record of her paternal Scots-Irish grandfather’s presence after his wife’s 1845 death, an era thick with anti-Irish sentiment among New Englanders.

In the portion of papers that remain with me, I’ve identified two motivations for the searching: Formally, to link the family to big historical moments in United States’ settler history. Informally, to fill in the gaps where only names identify family in almost every generation who had “gone missing.” If choice played a role in their decisions to leave the family orbit, these were coerced choices where all options came with a threat linked to staying and a cost linked to leaving.

A trio of nieces, including the cousin I was working with, committed to updating Edna’s Daughters of the American Revolution and Mayflower Society membership applications. The original forms drew on Edna’s formal research documenting her generation’s connection to David Clark, a Massachusetts-based Revolutionary War private, and outlining a Mayflower Society path from David Clark’s mother Mary Wild to John and Priscilla Mullens, Mary Wild’s great grandparents. Her nieces’ work added contemporary generations to this lineage.

I am an outsider to both genealogical organizations, each requiring proof of bloodline descent. I am, simultaneously the one among that small group of cousins who can carry forward the oral stories and lived experience of that Tracy home place.

I find myself searching out stories for the ancestors who come to me via biodude – from the grandmother and aunt I might well have encountered in Mom’s hometown to the the cousins who will talk with me, even on to 17th century settler class of Jamestown.

And I remain an outsider – someone who will never be present – to the marital children biodude raised. As I peruse community stories and newspaper records, it seems they and their children share his conservative political and evangelical religious views.

Perhaps my desire to be missing from that family is not so different from either Amanuel’s as he lost his children to his wife’s Puritan-descendant family, or Puzzy’s as home became unsafe with his oldest brother’s attitudes and angers

*** *** ***

Adding Mom’s death record to Ancestry in April 2005, I learned Puzzy had also died. The Houston National Cemetery recorded his burial as 23 September 1998.

Sitting with his headstone as my back rest, at the end of 2005, I scribbled notes about the difference between having an uncle who was missing and one who had gone missing.

The uncle who was missing took up space in my life as a specter – foreboding and haunting, fixed and hexed, forever and only missing. This was the uncle who turned away from his queer goddaughter, leaving her – that early me, with the dry drunk oldest uncle whose homophobia and brawls drove Puz from the homeplace when the men were grown ass adults. For the specter, this goddaughter wasn’t enough, she couldn’t be trusted – didn’t deserve? – to know his location.

But, as he told me time and again through stories and mentoring, I had been enough. And in this second mindset, my fairy godfather had gone missing. This gone missing uncle existed through that perfect tense verb construction in which a particular action, missing, had occurred over time and continued into the present. In the perfect tense, a human would make choices; therefore, my uncle would have chosen physical exile, and I could choose him as a psychological presence continuing to spur me on. And I could – I did – choose to invite the lingering effects of our time together to remain a pulse in my life.

In going missing he might well have been, as Gram’s 1990s obituary claimed, an artist living in Laguna Beach. Graveside in Houston, he could be the darkly humorous, sparkling-eyed, gay artist who was a life force in Houston, someone finding new loves, words, friends, and community.

He made a life by going missing. And he also chose to be missing, that first construction, in his decision to die by completing suicide rather than fade out of life with cancer. That his death certificate includes the full names of both parents speaks to me of their presence yet in Puzzy’s bones, heart, and soul that 18 September 1998 that he ended his physical presence.

*** *** ***

I might well be the only Alexander-Evans-Stafford-Svelstad who has refused to go missing. And I might well be the first one in the small Poole-Mischke genetic pool to make that same refusal.

As the maker of my own story, my own Ancestry rhizomatic landscapes where I trace out each family, and forever engaged in making my own damn adult identity, now it’s time to figure out how – and why – to place these stories into genealogies, and most of all, to make them stories live outside my head.